Works of love for neighbors in need

Quilts are handed out to the Busiswe Luncheon Club, South Africa. The club is a group of elderly who meet daily to sing, share meals, and support each other while their families are working and in school. All photos: CLWR

LWF partner Canadian Lutheran World Relief adapts “We Care”-program

(LWI) – Empowerment instead of charity: LWF’s related agency Canadian Lutheran World Relief (CLWR) is adapting its “We Care” volunteer project, replacing shipments of in-kind-donations to communities in need with non-material support. Growing concern about climate change and economic impact on local markets, together with logistic considerations, were driving that decision.

CLWR with it’s “We Care” program is the diaconal arm of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada (ELCIC) and the Lutheran Church – Canada (LCC). “We Care” was a volunteer activity by Canadian Lutherans, who donated relief items, food and even medication to people in need. LWF World Service programs and LWF member churches were among those receiving shipments of We Care.

Students from the highland community of Jinotega, Nicaragua holding their We Care kits, 2015.

LWF World Service director Maria Immonen welcomed the decision. “Refugees and internally displaced people have lost so much, not only their possessions, but also the dignity of being able to influence their own lives,” she says. “Material aid, while sometimes necessary in extreme situations, further reduces a person’s right to make decisions, which can lead to passivity and hopelessness.”

Your love for the work we do together and the people receiving the gifts is more valuable than we can express.“Our country programs have asked me to extend warm, personal greetings to every person who has been involved in either quilting, putting the shipments together, planning the content or any other element of this work. Your love for the work we do together and the people receiving the gifts is more valuable than we can express,” Immonen says.

Sharing warmth, and a craft

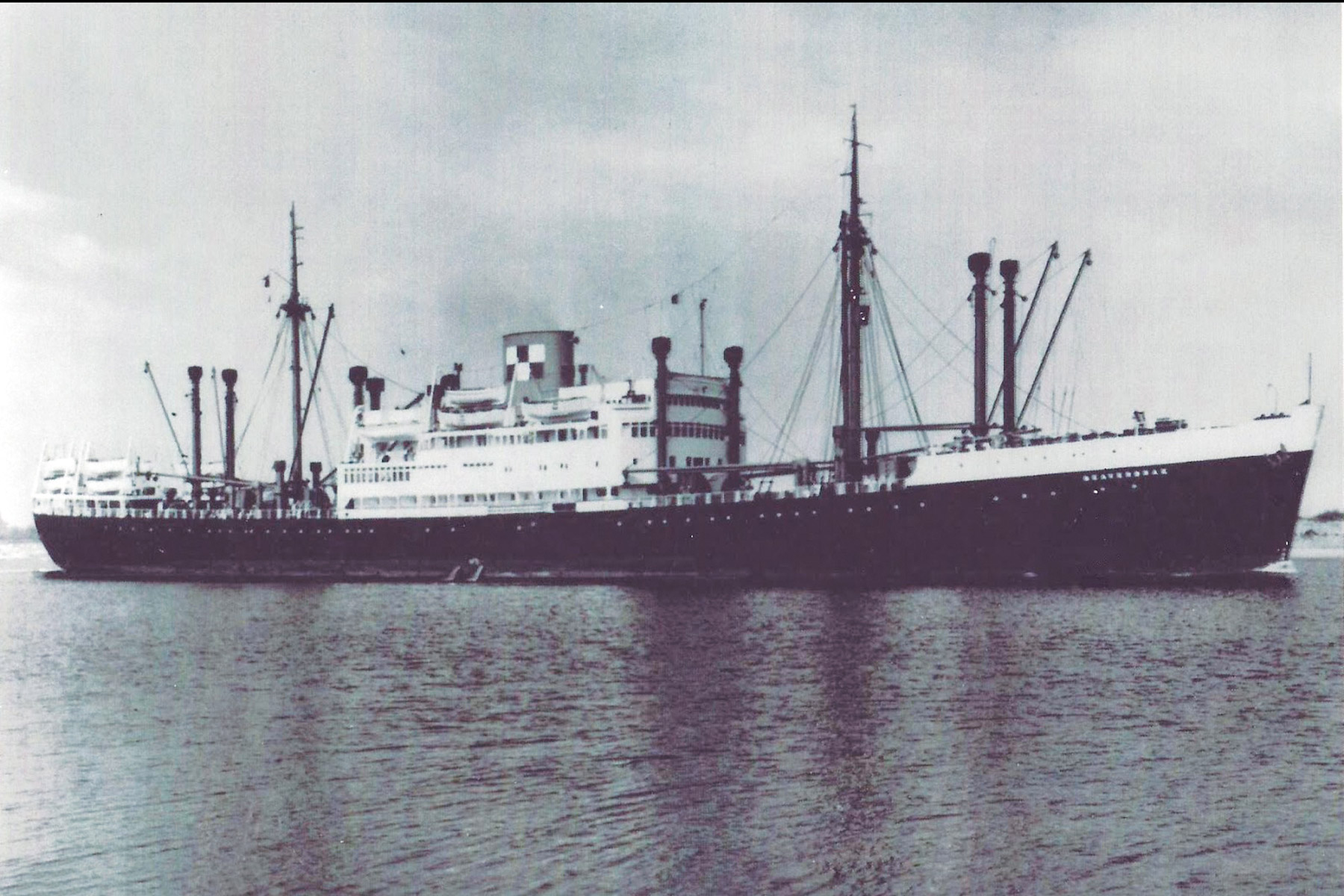

The “Beaverbray” was the cargo ship which brought European refugees to Canada, and Canadian quilts to warn-torn Europe.

The heart of “We Care” has been a traditional Canadian craft: hand-quilted blankets, carefully sewn in countless hours by members of Lutheran congregations throughout the country. After the Second World War, there was a need for warm blankets in Germany. People in Canada would gather and sew, and the same boat, which brought refugees from Europe to be resettled in Canada, would then take the blankets and other supplies back to the postwar countries. “These were things that were urgently needed, and could at the time not be produced in a war-torn region,” says Rev. Dr Karin Achtelstetter, Executive Director of CLWR.

Members of Mount Calvary Lutheran Church’s “Charity Quilters” group work together to tie knots in a large quilt. Photo: Church Red Deer, Alberta, 2014

The shipments would later also include clothes, school kits, food and hygiene items. After there was no longer a need in Germany, the shipments changed direction: We Care sent quilts, and other relief goods, including toys, medication and laptops to World Service country programs in Angola, Cameroon, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Hungary, India, Jordan and Jerusalem, Kenya, Liberia, Nicaragua, Uganda and Mauritania, among others.

“Our country programs and emergency operations have been happy to receive the shipments,” says LWF World Service director Immonen. “The quilts were obviously special gifts. Through them, an entirely different element of hand-made human contact came into being.”

Palestinian boy with a We Care quilt, West Bank, 2007.

But the program also had a benefit for those who were giving. Quilting groups became a place to gather and share about the situation of those the quilts were intended for. Achtelstetter recalls the “bailing days”, when volunteers would meet and pack up the donations. “On one end of the quilt bundle, there would be a school child, and on the other a grandma. These activities helped build communities,” she says.

Change in the aid sector

The longer distances to receiving communities, and a rising awareness for climate and economic issues also led people to ask questions about the sustainability of the model. “People in the congregations would ask if this was really the best way to deliver aid,” Achtelstetter says. “Are we shipping things people need? Are we undermining local markets? Are the high transportation costs not better invested elsewhere? Is this good for the environment?”

At the same time, the aid sector shifted to a rights-based approach. Instead of giving in-kind donations, humanitarian organizations are more and more handing out cash grants or cash cards, giving people who already lost so much a choice of what to buy, and a bit of control over daily life choices. “Today, shipping relief goods across the globe is an outdated charity model,” Achtelstetter says.

Last shipment, ready to go: Cody Cleave, We Care coordinator; Ian Mair, We Care assistant; and Benoit Grise, a volunteer, stand in front of a fully packed shipping container at the Winnipeg warehouse. This shipment is headed to Lesotho and will be the last We Care shipment to go overseas. Winnipeg, Canada, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the discussion, as many members of the quilting groups were people at high risk of infection, and the groups had to pause their gatherings. In a unanimous decision, the CLWR Board voted to end the current practice and replace it with a more sustainable and rights-based approach. “It’s not the end of We Care, but of shipping commodities,” Achtelstetter emphasizes.

Reach out to local communities

The decision was met with a lot of understanding and support in the Lutheran congregations and among the clergy in Canada, Achtelstetter says. Still, there was a concern about also losing the sense of community and shared purpose, which the program had brought to Canadian congregations.

“This is more than just a relief item,” Achtelstetter says. “It takes a very long time to make a quilt. On the other end, you receive something handmade, with love and care – this is more than just a blanket. How can that love be captured in a different way in the future?“

The “Bailing Days” were an occasion for volunteers in the Canadian congregations to gather and share about the people their relief packs were intended for.

Preparing the last shipment, with all the quilts still sitting in the warehouse might have indicated new ways to continue the old model: The Mission to Seafarers indicated that they needed the warm quilts. Others were given to people in need, in nearby communities in Canada. Some groups discussed continuing the craft and selling the quilts to raise money for overseas projects.

“It’s a similar model as was applied with the Canadian Foodgrains Bank”, Achtelstetter says. “Instead of shipping the grain, farmers would dedicate a plot of land to a project, and give what they earned from the harvest to a cause.” With many Canadians sponsoring refugee families, or having supported We Care for decades, there is a high awareness about the situation of refugees and in regions of conflict and natural disaster, Achtelstetter adds.

“The handmade quilts are works of love. We really hope that the idea of supporting our neighbors far away can continue through this activity which gathers people around our common humanity,” Immonen adds.

Upon receiving quilts during the formal service, members of the Busiswe Luncheon Club in Tembisa, South Africa (2017) break into joyful song and dance.

New global realities have also changed the setup of the quilting groups. In a congregation in west Toronto, part of the group are women from South Sudan. “They have similar traditions, but different quilting techniques,” Achtelstetter says. The two traditions will now make up a new generation of quilts.