The youngest victims of conflict

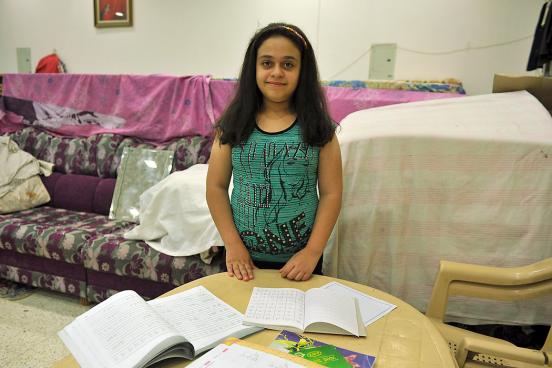

Caption: Shemaa (8) and Bushra (9) getting ready for school. The girls and their family live in a communal shelter with 31 other people. Photo: LWF/ Seivan Salim

DOHUK, Iraq/ GENEVA, 20 November 2015 (LWI) – At age 12, Besna has already learned what it means to lose your home. “I miss my books and things, my video games and my laptop,” the girl with the green T-Shirt says. “At home, I could just go out and play with my friends. But I have no home here, and I don’t know where my friends are. I heard one of them lives in France now.”

Besna is the eldest of the six children who live with their families in St Peter and Paul church, Dohuk. The 51 people who share one room have fenced off their living areas with donated furniture to have some space of their own. What looks like children were trying to build a hut with some furniture, has been the dire reality for these eight families since Mosul was taken by IS militia in June 2014. There are infants and adults, parents and grandparents, all sharing two bathrooms and a small kitchen.

No school, no place to play

Like everybody else sheltered in this place, Besna has dark circles under her eyes, testament of exhaustion and a lack of sleep for a long time. “It is very loud here,” she says. As the cold season approaches, the people are spending more and more time indoors. Although the school term started two months ago, the blue backpacks lie unused on the sofas and makeshift shelves.

After being home to displaced people for months, many schools in Dohuk are in need of repair. The remaining classrooms are crowded with local children and those from displaced families, who learn in two shifts each day. Until the situation is resolved, Besna and the other children in St Peter and Paul will have to study on their own.

“This situation is most difficult for the children,” Nura, a mother to two other children in St Peter and Paul, says. “They don’t have a place to play, to do homework, they can’t sleep.” When she fled Mosul, her youngest child was 14 months old.

Nightmares from the shooting

About an hour from Dohuk in the rural area of Chamanke, Aqela Ibrahim is trying to put her nine-month-old baby niece down for an afternoon nap. The baby girl was born in the shelterwith no medical assistance to her mother, save for the other women who share the space. “Thank God we are still alive,” Majeed Alli, the child’s father, says. “”When we fled there was shooting and bombing, my [other] daughters were scared. At night they still cry out in their sleep, they stay awake because they fear the nightmares.”

The living situation in Chamanke is similar to Dohuk’s, the only difference is that families here have partitioned rooms with high walls of cardboard and plywood. A TV in the center of the communal space is the only entertainment. Wailing children, scolding adults and the TV news can be heard everywhere.

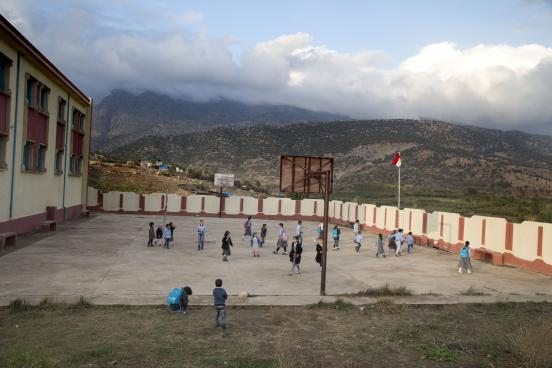

As Majeed Alli speaks, his elder daughters disappear behind one of the cardboard doors and return soon after in grey school uniforms and blue backpacks: The displaced children attend school in the afternoon, as the local school cannot accommodate all of them at the same time.

“We are lions”

“Who are you?” the teacher asks the students by way of greeting. “We are Kurdish! We are lions!” the children shout back with one voice. The 70 students in the afternoon classes are from families which were displaced from Sinjar. Teacher Saad Hassan Ahmed is a refugee in his own country himself; he even knows some of the students from home. “It is hard for them,” he says. “They are not learning well.” Many students live in congested communal shelters; there is no quiet space for homework.

The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) provides the students’ families with food, clothing and sanitation items. The United Nations egives the students, school uniforms and the trademark blue backpacks containing books and stationery. But while the material aid helps to ensure their school attendance, there is no undoing the memories the children carry with them. According to the teachers, they often talk of home, of friends and toys they left behind, and of the things they experienced when they had to flee.

“Months later they still remember vividly,” Ahmed says. “My children sometimes shout in their sleep: They’re coming! We passed dead people when we fled, and they asked me: ‘Why are they sleeping?’” All the teachers in the school noticed the children’s fatigue, they are often tired and have trouble concentrating, Ahmed adds. “We teachers are traumatized; we forget things because of what happened. Imagine what it is like for the children.”

LWF is supporting displaced families in Northern Iraq with food, sanitary items and other relief goods such as winter clothing. LWF also runs women-friendly spaces where women and children can engage in arts and crafts and receive psychosocial support. Together with its local partner, the Jiyan Foundation, LWF provides counseling and psychological support for traumatized people.